Their legacy is assured.

With Bill Mather-Brown’s departure from this life on August 17 and Gary Hooper’s five days earlier, the curtain quietly drew on our last living links to the Australian Paralympic Team of 1960.

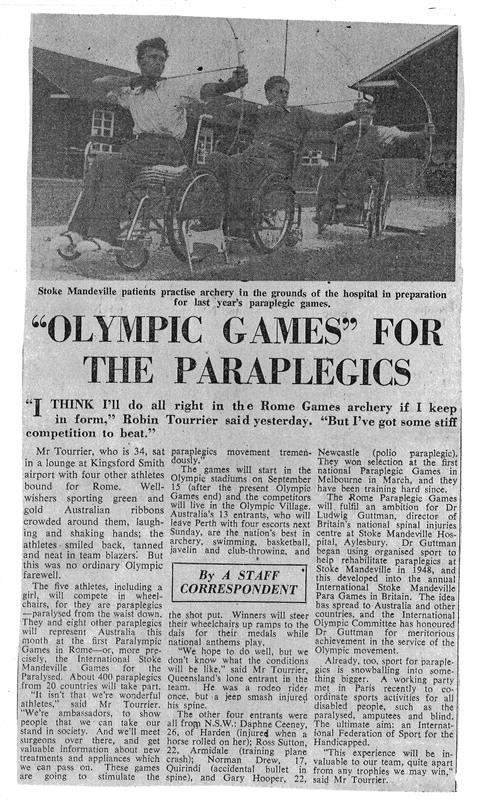

The first Paralympic team. A group of 12 athletes, who along with their support staff, etched an incredible story of resilience, enthusiasm and pioneering spirit. The first great narrative in Australia’s unique and wonderful Paralympic Games history.

How fitting that Hooper’s and Mather-Brown’s final days were spent on opposite coasts. Unaware many may be, but theirs and their teammates’ impact reached millions of lives across the continent.

From the Top End, from where hailed Australia’s only Torres Strait Islander Paralympian, Harry Mosby, to Bunbury in the deep south-west, home to Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Games hopeful Sean Pollard – and everywhere in between – generations of Australians with a disability found a home in sport in the wake of the team of 1960. So, too, can countless Australians who have been challenged to be better in their everyday lives trace that inspiration back to our original Paralympians.

No longer are they with us. However, between 2009 and 2020, the National Library of Australia and Paralympics Australia worked together to produce the Australian Centre for Paralympic Studies oral history project, preserving the remarkable stories that came to define Australia’s Paralympic character.

The trove of 57 publicly available interviews reveals scores of first-hand accounts and anecdotes, including from seven of the 12 team members who competed at the Rome Games in 1960. They provide a priceless insight into the unique dynamics within the team, the ways they approached enormous challenges and how far the Paralympic Movement has come in the decades since.

Additionally, a video produced in 2010 by the then-Australian Paralympic Committee to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1960 Paralympic Games, shines a light on our very first Paralympians.

Australia’s 12 athletes at the 1960 Summer Paralympics were:

- Daphne Ceeney

- Gary Hooper

- Robin Tourrier

- Kevin Coombs

- Frank Ponta

- Ross Sutton

- Bruno Moretti

- Christopher O’Brien

- Kevin Cunningham

- Bill Mather-Brown

- Roger Cockerill

- John Turich

The team officials were:

- Dr David Cheshire (Manager)

- John Johnston (Physio)

- Kevin Betts (Remedial Gymnast)

- Fred Ring (Nurse)

Kevin Coombs OAM PLY, the first Indigenous Australian to compete at the Paralympics, was interviewed for the history project on August 4, 2009.

“Yes, I travelled on a British passport. When I look back now, it’s sort of… it was a bit shocking, I suppose,” Coombs said.

Born in 1941 in Swan Hill, Victoria, Coombs acquired paraplegia at age 12 when he was accidently shot in the back while out shooting rabbits. He was introduced to sport while in rehabilitation in Melbourne.

“Before I came to Melbourne, the biggest place I ever went to was Mildura,” he said. “And in Melbourne, well, you know, you were in the hospital ward, and you don’t see much there. So, it was a big eye-opener to go and meet so many people from different nations around the world [at the Rome Paralympics].”

Coombs competed in the first Australian wheelchair basketball championships in 1960 and was selected there to represent Australia in Rome. He recounted stories of how the players raised money for the trip.

“Well we, say for instance, when Jack Kramer’s tennis troupe was out here, like Pancho Gonzales and Pancho Segura and Lew Hoad and all those people he had signed up, they played tennis at the old Olympic swimming pool here in Melbourne and we used to shake tins outside. ‘Help the boys to Rome,’ you know, we’d be out there shaking tins … any way we could get a quid.”

Coombs provided insight into some of his 1960 teammates, including Frank Ponta, later a fellow Australian Paralympic Hall of Fame member, who was born in Perth in 1935, the eldest of nine children. Ponta acquired paraplegia during an operation to remove a tumour in his spine when he was 17 and was introduced to sport while in rehabilitation at Royal Perth Hospital.

“Frank Ponta has been a lifelong friend of mine,” Coombs said. “I love the guy… He’s a marvellous fella and he’s a real knockabout bloke. He had Italian parents; he was very good at sport. He was a very good basketballer, very good at field events and stuff like that. He’s just a decent fella.”

Coombs spoke of Bill Mather-Brown: “Bill was always the goody-two-shoes of the team. If he was going to a movie he’d leave halfway through and say he’s got to go to bed. … He was always saying, ‘You blokes have got to toe the line and look after your body…’.

Of John Turich, Coombs said: “Johnny, the late Johnny Turich. If I could just tell you this brief story; Johnny Turich was a huge man, I think he was of Croatian or Yugoslav descent. He was one of those big fellas that [suggested] ‘If I did it, it’s got to be right.’

“Anyway, he decided to buy a dozen business shirts, and they were all beautiful silk, handmade and all that. Anyway, we’d put it on to fly because everywhere we went we had ties on, even sitting 12 hours in a plane, you had to look smart and be an ambassador for the country. And Johnny was saying how good we look.

“He said, ‘Oh, they were handmade’. Anyway, he took the jacket off and one arm came with it! All his shirts fell to pieces.”

Recalling the flights to Rome, Coombs recounted: “We got on the Super Constellation, I think it was TAA, and we flew to Perth, and stayed a day-and-a-half or two days there. Then our next stop was in Singapore and we were there for two days.

“I was wheeling down the street in Singapore with ‘Australia’ written across the back of my T-shirt, part of our uniform. I was wheeling along and I see all these people following me, and I thought, ‘Oh geez.’

“Because of the White Australia policy, they were saying, ‘How did you get into that country?’ They thought I was Indian, like a lot of Indians in Singapore, and they wanted to know how I got into Australia.”

Gary Hooper MBE, who was inducted into the Australian Paralympic Hall of Fame last year, in his interview with the oral history project reflected on 1960: “I thought it was just … how lucky am I to be here? I think back, would I have made it as a runner? I don’t know. Would I become [like] Herb Elliott, John Landy, you know, just maybe I would’ve. I mean I was only 12, so…”

Hooper was referring to when he contracted polio, leading to paraplegia. He later attended the Mount Wilga Rehabilitation Hospital in Hornsby in Sydney, where he became involved in wheelchair sport and excelled. At Rome 1960, he won a silver medal in javelin.

“Well, it wasn’t really set up for wheelchairs,” he said of the accommodation at the first Paralympics. “I never forget one of our blokes, it could have been Billy Mather-Brown, came up with something like, ‘God, that water’s hard to get to in the wash basin’. He was trying to have a drink, but it wasn’t one of them at all.”

Mather-Brown had mistaken a bidet for a wash basin.

“So, I said to Bill, ‘Go and talk to Bruno and he’ll tell you what they are’, [Bruno Moretti] being Italian. So, anyway, he went away in disgust after that!”

Hooper talked about the accommodation at the Rome Games and how Kevin Betts, the much-revered founding father of wheelchair sports in Australia, would help the athletes up the stairs.

“There were about 10 stairs up before you, then it flattened out,” Hooper said.

“Bettsy was strong, he was very, very strong. He’d virtually get hold of the back of your wheelchair and pull you up, or you’d jump out of the wheelchair and bum up the steps.”

Bruno Moretti was born in Ivanhoe in Victoria in 1941 and he said that, according to his mother, “they dislocated my spine at birth.”

For Moretti, like most others in the team, Rome was his first overseas trip and first time on an aeroplane.

“Well, see, back when I went to Rome, you had to be good at four events to be selected,” Moretti said.

“If you couldn’t do field events and you couldn’t do table tennis, you couldn’t do basketball and other things, you weren’t even looked at. You had to be up to world standard in those events for you to go to be selected. You weren’t specialising in one event.”

Moretti took annual leave from work to represent Australia at the 1960 Games, where he won a silver medal in Para-table tennis. Upon his return, life looked a little different.

“Because I’d been overseas [representing Australia] and because I was a keen Geelong supporter, I used to go and watch the games, and I used to go in the rooms after the game,” he said. “Billy Goggin and Doug Wade and ‘Polly’ Farmer, and all those players that were playing in that era, I got friendly with them, you know.

“… To raise more money, we used to play the VFL footballers back then, put them in wheelchairs and play basketball. I mean, some of the guys, like Bobby Skilton and stuff like that, they were really great fun to be with, and even though they were great footballers, they were also great people.

“We played a lot of them. We played Carlton, we played Collingwood, we played Geelong… Raising money. You might get two or three hundred people come along. Well, that was all money that we didn’t have.

“It’s interesting because once you start moving in those circles with other sporting people, it opens up other opportunities for you as well. I mean, we played the Harlem Globetrotters in wheelchairs as well. We put them in wheelchairs. In fact, just across the road here.”

Moretti said the spirit in the team of 1960 was high, despite the athletes having spent “virtually no time at all together”.

“You’ve got an aim, all heading in the same direction and therefore, you’re all looking to help one another rather than hit one another, you know. You knew what was going to take place, but you don’t sort of appreciate it until such time you get in there, and it’s a good feeling, it’s a great feeling. Because you’re there representing Australia. Representing your own country for whatever reason is a great feeling.”

The only woman on the team was Daphne Ceeney, who became Daphne Hilton post-marriage. She acquired paraplegia after breaking her back in a horse-riding accident in 1951 at the age of 17. Some years after her accident, she spent a life-changing year at Mount Wilga Rehabilitation Hospital.

“I was scared stiff,” she said of trying to play sports. “I didn’t know what was going to be ahead of me and I didn’t know how I was going to face it. But it was absolutely an eye-opener for me and a new start in life.”

Ceeney attended the NSW trials, the first of its kind, and was selected to compete at the national trials in Melbourne. It would be her first time on a plane. After performing well in various sports, “they advised me that I was selected [for Rome], which was very exciting.”

Ceeney said her hometown of Harden-Murrumburrah got behind her fundraising activities.

“All sorts of parties, street stalls, dances, balls. It just covered about every aspect there was. Family, friends … they had street stalls and what have you to raise funds for me.”

During the Games, Ceeney recalled: “We explored all of Rome. We went to the Colosseum and the various fountains. We even had a coach ride, which was gorgeous, on an old horse and I think the driver was about a hundred! It was definitely an eye-opener for the future.”

The town celebrated Ceeney’s return.

“There was an open car parade through the streets, a dance in the evening, photographs being taken and everything else.”

More broadly, she said, there was a shift after the Rome Games in the way she and her teammates were looked at in their everyday lives.

“They treated us as athletes. It was good from the point of view that you were acknowledged as a person again, where before I think people sort of looked on you as second-rate citizen.

“They never referred to me as being disabled and never looked down upon me as being disabled, which I thought was very good.

“I think it’s because they got to know more about [disability] and realised that we’re just the same people. We’re just a little bit different in in our circumstances.”

The Games was life-changing in a different sort of way for Chris O’Brien, who competed in shot put and javelin.

“I met a girl from the English team that came to [Rome], she was a very good table tennis player,” O’Brien told the oral history project of his then-future wife, Marion Edwards.

“We wrote to each other after the Games and then she came out here with the English team in 1962 [for the Empire Games]. We wrote to each other after she went home and I eventually proposed to her by letter. I said, ‘Come on back to Australia if you can afford it.’

“So, she came, and she lived with us for a while and eventually we got married.”

The couple had two kids and Marion went on to represent Australia, teaming up with Ceeney at the 1964 Paralympics to win Australia’s first Para-table tennis gold medal.

Bill Mather-Brown, in his oral history project interview, spoke of the successful fundraising country trips undertaken by the athletes in their month or so in Western Australia before heading to Rome.

“That was a good idea because people weren’t used to disabled sport or disabled sportsmen, nor wheelchairs,” he said. “And so, when we played in country towns, they got an idea of just what disabled people were about and what disabled people could possibly do.

“We had terrific support from places like Albany, Geraldton, Kalgoorlie. We went everywhere. It acclimatised people to what paraplegia and quadriplegia was. It had educational value and was of great value to the disabled in this state.

“People started to, instead of saying, ‘You’re out of hospital for the day?’ They started to say, ‘Did you win or lose last night?’ And that makes a big difference.”

For Frank Ponta, silver medallist in javelin and fencing, a key memory of the 1960 Paralympics was a particular party, a second party with members of the American team, that ended up becoming a rowdy multinational celebration.

“Well, every time you went for a meal you got a small little bottle of wine with your meal,” Ponta said. “So, what we did, we saved all this wine up and stashed it away.

“We said to the Yanks, ‘Look, we’ll have a party after the Games’ and … was it a party, oh yeah. Nobody could understand one another because they were all different nationalities. But it was a party and a half.”

The drinking age was 21 in those days and, as it happened, Kevin Cunningham turned 21 just before the Games. Cunningham had been involved in a car accident in 1957 and undertook rehabilitation at Shenton Park Rehabilitation Centre in Perth.

“As Sir George Bedbrook (regarded as the founder of the Paralympic Movement in Australia) said, ‘Until you can get up off the ground and into your wheelchair, or off the ground up on your crutches, you’re not going home’. So, unless you were fit enough, you didn’t go home. We worked our tails off to make sure when you went home you stayed home.”

Cunningham said he increased his chest size by 10 inches at Shenton Park, due to the weightlifting program and other sports there. He was selected for Rome 1960 to compete in wheelchair fencing and wheelchair basketball.

“We’d tour around Western Australia, going from town to town, giving demonstration games of basketball to raise money,” he told the oral history project.

“We rattled tins at footy games at Subi Oval and all sorts of places and we were always up against it. But I remember one meeting we had at a function we went to at Government House. The then-premier, Sir David Brand, said, ‘How’s the money-raising going, Kev?’ And I said, ‘Well we’re up against it’. He said, ‘No, you’re not because whatever you need, I’ll supply’.

“That was the start of a good relationship between the sports – wheelchair sports – and the [West Australian] government. And it’s gone on pretty well since then. That’s what it’s all about; teamwork and support.”

May teamwork and support be the legacy of our pioneers of 1960.

“We had a great comradeship,” Cunningham said. “It was a great team. Teammates are teammates. It’s like any major sporting team –you become a part of a family and you never lose that sense.”

By David Sygall, Paralympics Australia.

Published 3 September, 2025.

Join AUS Squad

Join AUS Squad